How Video Compression Works

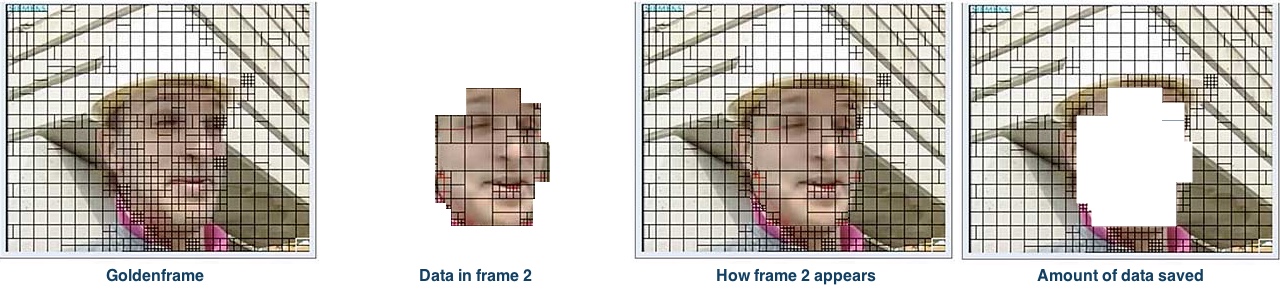

Creating videos is a very intense process. Most video uses the H.26X block-oriented motion-compensation-based video compression. In plain English, H.26X, rather than updating the whole frame at every refresh, splits the screen into horizontal and vertical grids and only updates the grids with changes. This means that the video takes up less space on a hard drive than H.264 and takes less processor-intensive resources to create the files. Cheaper processors were the part of the equation ten years ago, but the primary driver behind lowered price point and higher resolution in the last two years is better video compression.

This video is very different than what comes out of an analog device like a VCR or an older, analog camera. Older, non-HD video, just streams a series of pictures and sounds. It wasn't very efficient, but it wasn't sending a lot of data, so it didn't need to be.

Creating Video is called Encoding

On the inside, an IP camera and a smartphone are remarkably similar in design, but there's about a $1,000 difference in price.

IP cameras are more reasonably priced than smartphones because they can use lower-cost processors that offload the encoding work to a special chip in the hardware, rather than software encoding to do their work. Hardware encoding means that the processor in a camera can do one thing really, really well--create a video. A phone processor, on the other hand, is an expensive, jack-of-all-trades. A flagship smartphone has both hardware encoding and decoding chips in addition to general-purpose chips and the price reflects the additional hardware. A cheaper smartphone is less efficient with creating video than a processor that only can create a video, but it allows your smartphone to do just about anything.

Playing Video is called Decoding

When you go to play back video, you also need a processor because you need to be able to convert all those frames with only partial information back into something that looks like video.

If you wanted to connect a camera directly to a TV, you would need a decoder. For example, here's a 1 camera H.264 decoder that converts an IP camera stream into a standard definition TV stream. This device costs about 90 dollars, and again, downsamples the video back down to standard definition. This device will provide the processing power for your TV to receive the video images from the IP camera, and then package that data into a usable format for your TV, but it doesn't have the processing power to do so in HD.

NVRs are Decoders

There are two major cost drivers of NVRs: the hard drives and the decoder chips. You can buy an NVR without a hard drive, but buying a decoder isn't generally cheaper than buying an NVR without a hard drive. An NVR without a hard drive won't record anything, but it will allow you to decode and view cameras on a TV in true HD. Every NVR has a decoding spec (even if they don't publish it) and different manufacturers will vary in quality. The decoder spec lists how many cameras can be played back at the same time and at what resolution and framerate the processor supports. For example, our 4 Channel Admiral NVR allows you to decode one x 4K camera @ 30 frames per second (FPS), two 4MP cameras at 30 FPS, or four 1080P cameras at 30 FPS.